By Dulara Pramod

Introduction: The Comfort Trap

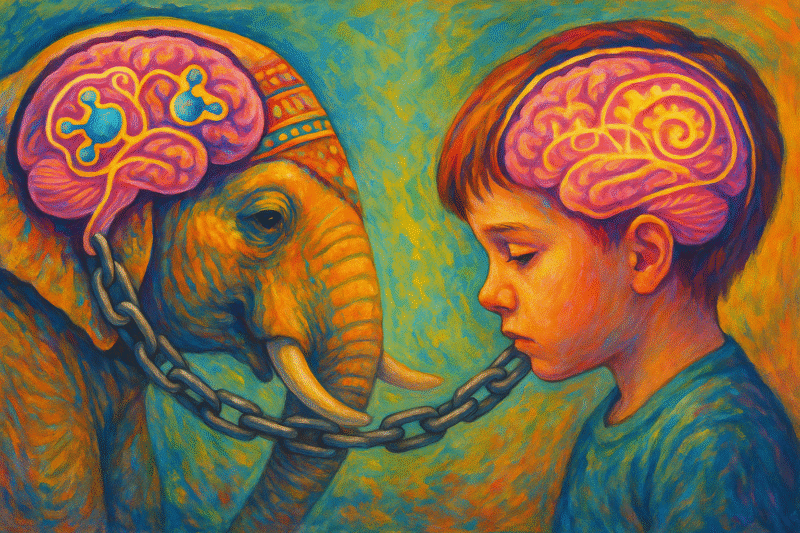

We live in a world that often mistakes comfort for care, and control for protection. In both the animal kingdom and human society, environments that appear nurturing on the surface can be deeply damaging underneath. The domestic elephant, a majestic creature brought into captivity and fed, bathed, and adorned with ceremonial glory, often lives a life far removed from its wild truth. Similarly, many children of toxic but materially supportive parents grow up with everything they need—except the freedom to be themselves.

This article explores the startling psychological, neurological, and emotional parallels between domestic elephants and such children. It merges insights from neuroscience, endocrinology, behavioral psychology, and trauma studies to understand how captivity—when disguised as care—can alter the brain, suppress the self, and shape a lifetime of struggle.

By drawing connections across species, this article aims to reveal not only the science behind suppressed development but also the emotional and philosophical cost of comfort without autonomy. Whether in elephant sanctuaries or family homes, the consequences of controlled environments ripple across lifetimes, influencing behavior, identity, and even intergenerational trauma.

Section 1: The Domestic Elephant – A Giant in Chains

1.1 Life in Captivity

Domestic elephants are usually separated from their mothers at a young age, a process that begins with breaking their will. Traditional training methods, often called “crushing” or “phajaan” in Southeast Asia, involve physical punishment, starvation, and isolation. While modern institutions may avoid such visible cruelty, the fundamental principle remains: control.

These elephants are then fed, bathed, and kept safe from predators. They live lives devoid of risk, but also devoid of autonomy. Their behavior becomes predictable, their spirit subdued. Most tragically, they lose the instinct to explore, form wild bonds, or trust their own judgment.

The psychological cost of captivity extends far beyond the physical boundaries. Elephants in such settings develop symptoms of psychological distress—swaying, depression, social withdrawal, and in some cases, even self-harming behaviors like tusk-biting and head-banging.

1.2 Neurobiological Impact

- Cortisol Overload: Captivity elevates cortisol levels in elephants, especially when they are restrained or punished. Chronic cortisol exposure leads to hippocampal shrinkage, which impairs memory and emotional regulation. High cortisol also impairs immune function and increases anxiety levels.

- Blunted Dopamine Response: Elephants are naturally exploratory and playful. Deprived of stimulation and choice, their brains begin to produce less dopamine, the neurotransmitter associated with pleasure, reward, and motivation. They may stop showing interest in food variety, games, or social engagement.

- Disrupted Oxytocin Patterns: Normally used to bond with their herd, oxytocin pathways are redirected to human handlers. This creates an unnatural attachment model based on submission rather than mutual trust. The oxytocin imbalance can lead to confusion, codependency, and trauma-bonding patterns.

- Amygdala Hyperactivity: The amygdala, which governs fear responses, becomes sensitized. Even small stimuli can trigger anxiety, making the animal more obedient but less psychologically stable. Studies on captive mammals show that amygdala overactivation can also lead to increased aggression or social withdrawal.

- Dorsal Vagal Shutdown: Chronic restraint can trigger the polyvagal “freeze” response. The dorsal vagus nerve shuts down social engagement and mobility, leaving the elephant immobile and dissociative—a neurological shutdown akin to fainting or emotional numbing in humans.

Section 2: The Toxic Parent – A Prison Wrapped in Love

2.1 Definition and Characteristics

Toxic parents aren’t always abusive in the traditional sense. They may appear loving, provide for every material need, and boast about their sacrifices. But beneath this generosity lies manipulation, conditional affection, and psychological control.

They love in a way that is transactional: “We gave you food, school, a phone—so we own your obedience.”

Typical traits include:

- Guilt-tripping: “After everything we’ve done for you?”

- Emotional invalidation: “You’re overreacting.”

- Control masked as care: Choosing their child’s friends, career, or even thoughts

- Suppression of individuality: “We expect you to make us proud.”

- Conditional affection: “We’ll love you as long as you behave the way we want.”

These messages create a distorted sense of love—one that ties worth to obedience, and identity to external validation.

2.2 Emotional and Cognitive Impacts

- Anxiety Disorders: Constant emotional monitoring causes the child to become hypervigilant. This maps directly onto heightened amygdala activity, where the brain is always scanning for parental disapproval.

- Low Self-Efficacy: When decisions are always made for them, children develop learned helplessness. They begin to believe they cannot act effectively on their own, even in safe environments.

- Delayed Identity Formation: The prefrontal cortex, which supports self-reflection and long-term planning, develops less effectively in children who are discouraged from thinking independently. These children may struggle to form a sense of self or to establish boundaries in adulthood.

- Blunted Reward Systems: Creativity, curiosity, and risk-taking are punished. As with elephants, dopamine release is reduced when exploration is met with criticism or fear. As a result, children may stop seeking pleasure or avoid novelty entirely.

- Suppressed Mirror Neurons: Toxic environments also reduce empathy and social learning. When parental figures model control instead of understanding, the child internalizes fear instead of connection.

Section 3: Hormones and Brain Chemistry – A Shared Biology of Submission

| Neurochemical / System | Domestic Elephant | Child of Toxic Parent |

|---|---|---|

| Cortisol (stress) | Elevated chronically from control and restraint | Elevated from emotional suppression and fear of rejection |

| Dopamine (reward) | Reduced due to lack of natural stimuli | Blunted due to discouraged exploration and creativity |

| Oxytocin (bonding) | Misattached to human handler | Confused mix of love and fear towards parent |

| Amygdala (fear) | Overactivated due to trauma | Hyperactive from constant emotional vigilance |

| Prefrontal Cortex (decision) | Underutilized | Undeveloped autonomy and critical thinking |

| Vagus Nerve / Polyvagal | Often stuck in “freeze” mode | Social withdrawal or emotional shutdown |

Section 4: After the Chains – What Happens at 18?

At age 18, most children are expected to become independent adults. For a child raised in a psychologically controlling environment, this is akin to unchaining a domestic elephant and expecting it to run wild.

Common outcomes include:

- Delayed maturity: Struggles with self-direction, emotional regulation, and boundary-setting

- Rebellion or shutdown: Some react with anger, others with apathy

- Creative explosion or collapse: Once-repressed creativity either bursts forth or remains buried under anxiety

- Troubled relationships: Difficulty trusting, attaching, or expressing needs healthily

Scientific Support

- Neuroplasticity studies show that early-life stress rewires the brain for threat detection, not for exploration.

- Attachment theory (Bowlby) proves that secure early bonds are vital for lifelong confidence and emotional health.

- Gabor Maté’s trauma work links suppressed emotions with long-term disease and dysfunction.

- Bruce Perry’s clinical work outlines how neglected or misattuned childhoods result in dysregulated nervous systems and impaired executive function.

Section 5: Philosophical Reflection – The Price of Comfort Without Freedom

Imagine two beings:

- One, a massive elephant, bathed, fed, adorned with gold—but never allowed to walk the forest.

- Another, a child raised with iPads, private tuition, and clean clothes—but never allowed to speak their truth.

Both will grow strong bodies.

Both may look impressive.

But inside, they are broken in the same place: their freedom to choose, feel, and become.

Care without freedom is not love. It is programming.

Love without listening is not nurturing. It is control.

True nurture does not stifle but liberates. It teaches responsibility through trust, not fear. It allows mistakes, not just achievements. It respects boundaries, not just behavior.

When we confuse material provision for unconditional love, we raise beings who perform instead of live. The emotional and neurological consequences can take decades to undo—if they are ever undone at all.

Section 6: How to Heal – Rewilding the Self

For Elephants:

- Sanctuaries that allow elephants to roam, bathe, socialize, and forage

- Reduced human interaction, unless chosen by the animal

- Enrichment that stimulates natural behavior (e.g., puzzle feeders, mud baths)

- Gradual re-introduction into elephant herds for emotional restoration

For Children Turned Adults:

- Therapy that unpacks childhood conditioning (CBT, IFS, somatic therapy)

- Reconnection with play, art, movement, and self-expression

- Learning decision-making through trial and failure

- Practicing autonomy in small steps and setting healthy boundaries

- Building relationships based on mutual respect, not obligation

- Journaling, expressive arts, and mindfulness to reconnect with the inner child

- Community support groups or mentors who model freedom, not control

Healing is not linear. For some, healing starts with silence; for others, with rage. But in all cases, healing is a return to the wild core inside—the voice that was silenced, the vision that was punished, the dream that was locked away.

Conclusion: Reclaiming the Wild

To truly raise a being—whether elephant or human—means to do more than feed, clothe, and protect. It means to honor their nature, encourage their voice, and stand back as they try, fall, fail, and rise.

In a world that values control disguised as care, the greatest revolution is emotional freedom.

Let the child paint.

Let the elephant roam.

Let them both remember: they were never meant to live behind invisible bars.

References

- Seligman, M. E. P. (1972). Learned helplessness.

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and Loss.

- Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory.

- Gabor Maté (2011). The Myth of Normal.

- Plotnik, J. M., de Waal, F. B., & Reiss, D. (2006). Self-recognition in an Asian elephant, PNAS.

- Sapolsky, R. M. (2004). Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers.

- Perry, B. D. (2006). Applying principles of neurodevelopment to clinical work with maltreated and traumatized children.

- van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma.

- Siegel, D. J. (1999). The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are.